I believe it was the Jedi Master Obi-Wan Kenobi who said in 1977 AD in a galaxy far, far away, “If you strike me down, I shall become more powerful than you can possibly imagine.” What was he talking about? How would he become more powerful if he was dead? Obi-Wan, perhaps, simply referred to becoming a Force ghost. Maybe, he was talking about more than his physical existence. What if Obi-Wan knew his “death” would be the catalyst to bring legitimate order back to the galaxy, that Darth Vader, with his death blow, was only striking down a man and simultaneously raising a movement, something bigger than Obi-Wan Kenobi himself. In the end, imagine the Empire fell because they sought to destroy people instead of rooting out a cause. Now, take this same theme, go back seventeen years to 1960, and insert the movie Spartacus. The Empire becomes, well, the Roman Empire, and the Rebellion becomes Spartacus. “But,” you say, “Spartacus is a man, and the Rebellion was a collection of people fighting back against tyranny!” Yes, you are correct to an extent. Spartacus was a man for part of his life – he was born into slavery and was purchased and trained to become a gladiator. It is during his training that Spartacus the man dies and Spartacus the movement is born.

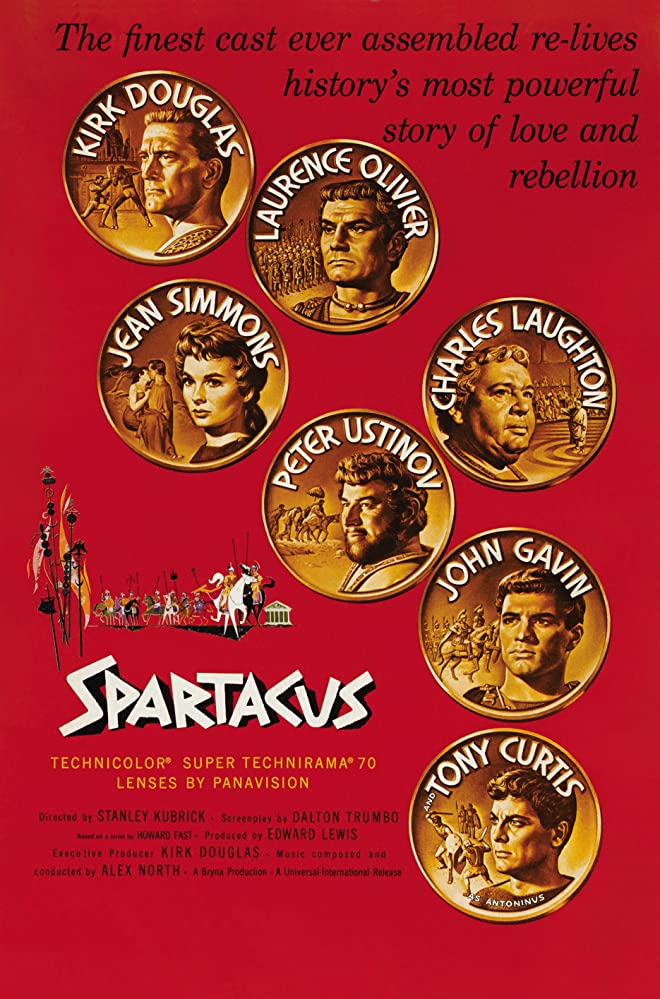

Spartacus sits at number 81 on AFI’s Top 100 American Movies of All Time. Directed by Stanley Kubrick and starring Kirk Douglas and Laurence Olivier in the top billings, Spartacus tells the story of a slave group fighting for freedom and the Roman zealot who seeks to establish order by squashing the rebellion’s leader, Spartacus. This is a film of great breadth, subtlety, and commentary. Released during a time in American history where civil rights were yet a dream, its themes of oppression, injustice, and superiority complexes are, unfortunately, as relevant today as they were sixty years ago. As 2020 does its best to unravel global society, we are witness to how poorly humans can treat one another and how uncivilized we are at the core once the veil of self-importance and fabricated truths is pulled aside. Film can be remarkable in these moments, because it serves as both documentation or allegorical record of what time has laid bare, showing that history does, in fact, repeat itself. If Spartacus’ quality is judged based solely upon its sprawling spectacle, the movie is worthy of a place on AFI’s list. When you include the thematic commentary and meaning behind what the slave rebellion embodied, the film solidifies its residence in the pantheon of hallowed cinema. For the purposes of this essay, though not to ignore the importance of raising the topic of equal and fair treatment, let us focus on the quality of the film and its place on the AFI Top 100.

Story

Based on the 1951 historical novel written by Howard Fast, Spartacus follows the titular character as he frees himself from slavery and then leads a march to freedom from Roman rule. Did Spartacus intend to be at the front of an uprising? Probably not. Spartacus did, however, believe in a better life and invested himself in creating that opportunity for others. The film’s progression saw Spartacus transcend beyond simply being a man as his name came to embody the pursuit of freedom and struggle against oppression.

The film bets its emotional investment on the powerful plight of the slaves’ struggle to earn what should be inherent before birth: freedom. That subject is wrapped in a cloak of political intrigue and the powerful’s desire to play God with the lives of others. Choosing sides is seldom easier as the Romans emanate pompous and despicable behavior. Only a redeeming act from an unexpected character in the film’s closing minutes can salvage any respect for that population.

Viewing the movie generates an experience across a spectrum. There are ebbs and flows throughout the movie as chaotic skirmishes and battles roll into intimate scenes of dialogue or reflection. It is an epic journey of three hours that ends up not feeling like three hours. As a viewer, you become invested in both the rebellion and the fate of the various Roman oppressors. Again, this story and the amount of awfulness existing in the world should no longer be relatable, but it is. That relevance must be acknowledged.

Visuals and Acting

Prior to watching this film, my experience with Spartacus lay with the Starz television series. It was a highly-stylized visual and auditory spectacle that I absolutely loved. The fighting was brutal and accompanied by an anachronistic hard rock soundtrack. The gladiators were shredded physical specimens, imposing and oiled in every scene. The actresses were gorgeous and seductive at every turn. Each episode left me with a quickened pulse and a little perspiration. The cinematic Spartacus, having released in 1960, could never match the same visual fidelity and auditory impact as its modern successors. What Stanley Kubrick accomplished with generating visual breadth and creating lasting imagery, however, is master-level craftsmanship. From sprawling sun-kissed landscapes to palatial roman estates, Kubrick establishes lush framing that is broad when necessary, like when needing to convey magnitude or season, and narrow when targeting focus on characters. Each scene is colorful and vibrant, moving smoothly from start to finish with steady and appropriate pacing. Like books that are easy to read, this film was pleasant to watch.

Setting and imagery can work miracles in bolstering mediocre acting. Spartacus, thankfully, does not suffer from lackluster acting and can, therefore, use its visual stylings to further enhance the film’s bountiful quality. With the likes of Kirk Douglas, Laurence Olivier, and Tony Curtis the center of each scene, quality acting would never have been a concern. Amidst the Hollywood heavyweights from that period, Jean Simmons, Charles Laughton, and Peter Ustinov (especially Peter Ustinov) were pleasant discoveries. Ustinov floated effortlessly through the film and seemed so comfortable with every line it was as if he was not acting at all; Ustinov’s Batiatus was the character I wanted in every scene because of the personality he gave the movie. He was a revelation.

At this point, it is worth noting that, as legendary as Kirk Douglas is, it was difficult buying into him as Spartacus. Douglas did not have the look of a well-fed and well-trained gladiator, but on those lines, nobody truly embodied what would, in today’s movies, be an accurately portrayed warrior built through months of professional training and coaching. Additionally, Douglas’ features are just too chiseled (that chin!); it was a distraction but not detrimental.

The End

Spartacus is a darn good movie, and its subject matter is too relevant to the world today. Aside from the message, the cinematic quality is top-notch. This is a prime example of an epic American film. There are moments that are both expansive and poignant, soft and intense. As a viewer, you are pulled in multiple directions and still receive a steady emotional ride. Spartacus is a film that should be experienced, and it deserves its reputation as a cinematic masterpiece.